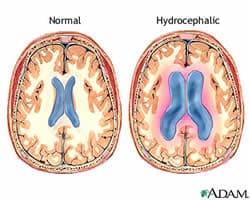

“This disease is devastating and costly (almost $2 billion annually), and current treatment options are extremely limited,” Calvin Carter, a student in the UI Graduate Program in Neuroscience told Medical News Today. “Development of non-invasive therapies would revolutionize treatment of this condition.”

Development of a new and revolutionary treatment option is exactly what Calvin Carter, first author, and Timothy Vogel, M.D. in the UI Department of Neurosurgery and co-lead author, hoped to accomplish with their recent study involving mice with hydrocephalus.

In collaboration with Val Sheffield, M.D., Ph.D., UI professor of pediatrics, director of the Division of Medical Genetics and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator and lead author on the study, the team focused on a specific group of immature cells otherwise known as NPCs, or neural precursor cells. These cells give rise to most types of brain cells, including glia cells and neurons. In particular, researchers focused on a particular subgroup of NPCs that have only been identified recently.

Found to be involved in the development of normal ventricles in former but recent research, these cells proliferate and die off in a precisely coordinated process. Sheffield and colleagues found that there was an imbalance in the proliferation and survival of these cells of mice in which hydrocephalus occurred. Both processes were affected; not only did cells die off at twice the normal rate, proliferation occurred at only half the normal rate.

With the cause now identified, researchers were able to move forward and find a method for treating the condition. In this instance, researcher found that treatment with lithium could bypass one aspect of the abnormal signaling and restore a normal proliferation rate. In turn, hydrocephalus in the mice was reduced.

“Our findings identify a new molecular mechanism underlying the development of neonatal hydrocephalus,” Carter said. “By targeting this defective signaling pathway in mice using an FDA-approved drug, we were able to successfully treat this disease non-invasively.”

And with this new information, Carter believes that the team’s goal of developing new treatments for hydrocephalus is possible. These treatments would be non-invasive and possibly more successful than the current methods. What’s more, identification of additional signaling pathways responsible for the development of this disease may be uncovered during further research, making treatments individualized for each patient and based on the cause of their condition.

“Our findings demonstrate for the first time that neural progenitor cells are involved in the development of neonatal hydrocephalus. We are also the first to manipulate the development of these progenitor cells and successfully treat neonatal hydrocephalus, a feat which opens the door to novel treatment strategies in treating this disease and other neurological disorders,” Carter said.

Related Articles:

- Critical Surgery Saves Baby Born with Heart Outside her Body

- Toddler to Be Big Sister’s Hero in Bone Marrow Transplant

- Cancer Survivor Gives Birth to Twins with Eggs Frozen 12 Years Ago