Even in developed countries, things can go wrong during delivery. In the case of hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, the condition is caused by a lack of oxygen to the baby’s brain. In developed countries, the complication is often caused by a knotted umbilical cord or a problem with the mother’s placenta during delivery. In developing countries, the complication may also be caused by anemia and malnutrition during pregnancy, or an untrained delivery.

Globally, about half of the infants with a severe form of this condition die; the majority of the other half end up with cerebral palsy or other lifelong brain injuries. Cooling of the brain can stop the process of dying brain cells and prevent or decrease the effects of hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, but the machinery needed to perform the cooling process is entirely too expensive for some; this is especially true for clinics, hospitals, and midwives in developing countries. And because of this, many of the infants born with this condition in developing countries die; an inexpensive, user-friendly device may soon change all that.

Johns Hopkins School of Medicine pediatric neurology professor, Michael V. Johnston, has spent 25 years studying ways to protect the brains of newborns. He has studied the use of hospital cooling units, which cost about $12,000 a piece, and he has spent some time visiting Egypt. It was there that he learned about the lack of medical equipment for babies born with oxygen-deprived brains. He learned that doctors were using cold water bottles and window fans to try and cool babies. Unfortunately, these efforts were rarely successful.

After arriving back in Boston, the chief medical officer and executive vice president of the Kennedy Krieger Institute, a center in Baltimore that helps children and teens with disorders of the brain, spinal cord and musculoskeletal systems, Johnston and Ryan Lee, a pediatric neurologist and postdoctoral fellow at Kennedy Krieger discussed the issue with Robert Allen. Allen suggested that Johnston and Lee present the issue to students in the school’s Center for Bioengineering Innovation and Design program.

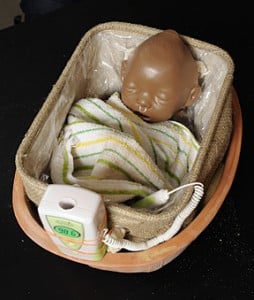

In 2011, a team of undergraduates accepted that challenge. Their goal was to develop an effective, inexpensive, user-friendly cooling system that would work effectively in dropping the baby’s body temperature. In the end, they came up with a clay pot, a plastic-lined inner basket, separated by a layer of sand, and a urea-based powder – the same powder that is used in instant cold-packs. In total, the device costs about $40 to make. What’s more, the device is so user-friendly that even parents can use it. All that’s needed to activate it is a little water.

The prototype, which is designed to accommodate a full-term newborn up to 9 pounds in weight and 18 inches in length, uses batteries to power a microprocessor and sensors that track the baby’s internal and skin temperatures. If the baby’s temperature gets too high, small red lights will flash; adding more water to the sand will increase the device’s cooling power. If the infant’s temperature gets too low, a blue light will flash; family members or nurses only need to lift the baby out of the device long enough for the temperature to rise a little. A green light indicates that the baby’s temperature is just right.

Two of the original inventors visited medical centers in India through a group called Medical and Educational Perspectives; this group has offered to financially support the project. Deemed the Cooling Cure project, three of the inventors – John J. Kim, Nathan Buchbinder and Simon Ammanual – have moved forward to try and bring the device to those that need it. A provisional patent has already been obtained, and the inventors are now working with Johns Hopkins Technology Transfer to link up with an international aid group to begin human trials in a developing region.

Related Articles:

- Three Person IVF Gets Go-Ahead from HFEA

- Study: Vitamin D Levels during Pregnancy has No Impact on Child’s Bone Health Later in Life

- Researchers Find New Method to Better Identify Women at High Risk for Preeclampsia