VIA bi.up.ac.za

If you knew that your child would be born with a birth defect, would it change your approach to having a baby? Would you decide to forgo pregnancy altogether and adopt, or would you search for options that could reduce the chances of the defect? Would the risk of certain types of defects influence your decision more than others? These are all questions that parents may be able to explore if a new study on genome testing proves to be a success.

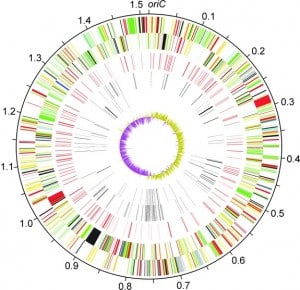

A decade ago, science embarked on the very first genome map. At that time, it cost around 2.7 billion dollars, and it took a great deal of time for the scientists to create the three billion letter genetic code map. Since that time, it has evolved drastically; a complete genome map can be created in just weeks for around a few thousand dollars.

Unlike genetic testing, genome sequencing allows scientists the ability to locate multiple mutations at the same time, which is a huge advantage when it comes to determining birth defect risks. And it is this advantage that The Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research team hopes to use during their $8.1 million dollar study.

The scientists plan to conduct a clinical trial that will take a whole genome sequencing approach to testing women and their partner for mutations that could cause rare, but serious conditions in their children. Some of those conditions are severe, and could shorten a child’s life (Tay-Sachs and Canavan diseases, for example). Others aren’t necessarily fatal, but they can affect the child’s overall quality of life (Pendred and Usher syndromes). But regardless of the severity of the condition, couples participating in the study will be able to make more informed decisions about childbearing and conception, long before either even happens.

“It’s more challenging to process and seek out information under the stress of pregnancy,” Dr. Ben Wilfond, a pediatric bioethics expert at Seattle Children’s Research Institute and co-principal investigator on the upcoming study told KomoNews.com.

Dr. Wilfond says that, if armed with the information before conception, parents can research the conditions that a potential child may be born with. At that time, they can research the condition, and what it’s like for parents living with children who have it. And, based on that information, they can decide how they want to approach having a child. He says that some may not change their decision to conceive naturally, while others may use techniques like in vitro fertilization to decrease the odds of passing along a genetic mutation. Whatever they decide, Wilfond says that they will have options.

“The important thing is to give people choices and make sure when they make those choices they have as good of information as possible about what might life be like with a particular condition,” Wilfond said.

And to help parents make those choices, Wilfond says that he and his team will be asking participants (pulled from couples in the Kaiser Permanente health plan in Oregon and Washington who have already requested preconception genetic testing) about their experience. They’ll be asking couples what information they found most helpful, how they felt the information was presented (as well as how they would have liked it presented) and how they used the information they learned.

“Some prospective parents will want information about each of these conditions, but others will only be interested in learning their risk for some of the more serious diseases,” Wilfond said. “This study will allow us to provide the information that is important to couples and counsel them about their reproductive options.”

It’s important for couples to know, however, that a mutated gene doesn’t necessarily mean a child will be born with a specific condition. For a child to develop a genetic condition, both parents must have the mutation, and both must pass on a copy of it to the child. Overall, it’s a likelihood of about 25 percent.

Couples should also consider whether or not they really want to open the Pandora’s box of genetic risks. Many parents who have had children with genetic conditions have found, after having their child, that they wouldn’t have changed a thing; their child is a gift that they treasure, in spite of (or maybe partly because of) their condition.

“Every child is a gift and has a purpose in life,” Katie Garberding, a mother from Seattle, told KomoNews.com. “I have a son with a genetic anomalies and he is truly a gift to not only my family, but to all that have the honor of knowing him.”

Related Articles:

- Twins born with a Single Body

- Decongestants May Increase Odds of Rare Birth Defects, Researchers Say

- Rare Birth Defect on the Rise, Study Says