When Finnegan Born-Crow was born, he was perfect (as all babies are). But at about three months of age, his mother, Nicole Born-Crow, started to worry that something might be wrong. Despite his normal development and growth up to that point, Nicole had started to notice that Finnegan had started to prefer doing things on just one side of his body.

Doing what most mothers would do, Nicole brought the concern to her son’s pediatrician. The pediatrician then referred Nicole and Finnegan to a neurologist, who would then conduct several tests to try and determine what was happening to Finnegan. Unfortunately, nothing seemed to pinpoint the root of the problem.

Then, right in the middle of the family’s vacation to New York City, Finnegan suffered a severe seizure. His family was absolutely “terrified.”

“It was terrifying. We had no idea what it was,” Nicole told FoxNews.com. “I had an idea of what epilepsy is. You think of violent shaking but not staring blankly into space. And he’d do that for a massive amount of time. He also got really shallow breath, and his eyes would start to tick to one side of his head.”

As soon as the family left New York, Nancy and her husband took Finnegan to University Hospitals Case Medical Center in Cleveland. There, doctors immediately put little Finnegan in the electroencephalography (EEG) unit where he would be under constant surveillance. It was their hope to discover exactly why the seizures were happening.

While there, hospital doctors attempted to control the seizures with medication. Unfortunately, nothing would work for very long, and Finnegan’s seizures were becoming more and more frequent – between three to five times a day, at this point in his treatment.

“For a while medication was working great, and at that point we thought it was under control,” Nicole said. “But then every couple of weeks a medication would stop working, so we’d up the dose or try something new.”

But after the third medication stopped working, physicians informed Nicole and her husband that Finnegan’s seizures were intractable – meaning there was a chance that no medication would ever work. The only shot at a normal life would be brain surgery.

“I thought, ‘Are you crazy? I’m not going to cut into my baby’s brain just for seizures.’ I was in denial,” Nicole said. But with Finnegan’s seizures continuing to increase in number (reaching between 50 and 100 per day), it became more and more apparent that something would have to be done – and that something was a new surgery, one that had never been conducted in the United States.

“They presented us with a plan,” Nicole said. “It was terrifying at first.”

But Nicole realized that she had to do something, so she consented TPO (temporoparietooccipital) disconnection on her one-year-old baby.

In traditional brain surgery for epilepsy (hemispherectomy), about half of the brain is removed. The idea is to stop the seizures by removing diseased parts of the brain. Unfortunately, there are also healthy parts of the brain removed, and if there is enough removal, or if crucial areas of the brain are removed, the patient may not be able to function correctly later on in life – this risk is even more problematic for older patients.

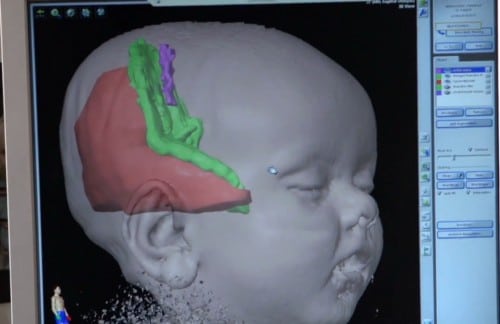

Dr. Jonathon Miller, director of functional and restorative neurosurgery at UH Case Medical Center wanted to try something different – TPO disconnection. The surgery would leave most of Finnegan’s brain intact – even the diseased portion – but it would hopefully stop the brain from communicating to the diseased area, thereby stopping the seizures. Armed with knowledge of where Finnegan’s brain was misfiring, this was done by placing just a couple very fine cuts into the fibers of his white matter (bundles of nerve cells that connect areas of the brain together) to disrupt the brain’s ability to communicate to the diseased portion of the brain.

“We’re able to leave the diseased brain in place, but allow it to be separate from the healthy brain,” Dr. Miller told FoxNews.com. “Not only do you stop the seizures, but you’re also allowing the normal parts of the brain to develop normally and develop normal functions.”

What’s more, Miller says that the healthy part of the brain can learn how to rewire itself and take over most, if not all, of the functions that the diseased portion of the brain would have been responsible for – if the surgery is done early enough in life.

“You really want to capture these things while the brain is still developing,” Miller said. “As people get older, it really does impede the development of cognitive function, because you’re having seizures come all the time…And an even bigger problem is that the brain can be passing functions on to the epilepsy portion of the brain, maybe where memory is formed or speech – even movement…So we, in effect, force the healthy parts to take over the areas that would have continued to produce epilepsy.”

And it would seem that Finnegan is definitely a testament to how well TPO disconnection works because, a year after his 10-hour surgery, Nicole says that Finnegan is doing extremely well. He hasn’t had a single seizure, and he is the happy little boy she knew before it had all started.

“He was amazing from the moment he woke up,” she said. “I was terrified they’d disconnect something that’d change him from the baby we had come to know. But he was totally normal; nothing was different except for the fact that he didn’t have seizures anymore.”

“There’s a large number of people in the country who suffer from epilepsy that may be curable, and people are afraid to undergo surgical procedures that could potentially have risk,” Miller said. “Hopefully by making [the surgery] less invasive, we make it a little more appealing and less dangerous so that we have better long term outcomes.”

Nicole also encouraged parents who have an infant or newborn suffering from epilepsy to talk to their doctor about TPO disconnection.

“I would tell them to run towards a surgery like this,” Nicole said. “I know parents are scared of any surgery, but epilepsy is not curable, and surgery [may be] the only fix for it. If you think your child is a good candidate, it’s great because there are so many children who aren’t.”

To watch the full video on Finnegan’s story, please visit Rainbow Hospital’s site.

Related Articles:

- Gene Deletions Found to Be More Common in Autism

- Study: C-Sections and Natural Births Have Equal Complications When It Comes To Twin Deliveries

- Toddler has Parasitic Twin Removed From Stomach