In this ever-changing world of technology, science, and medicine have grown by leaps and bounds over the past decade or so. But some of the most incredible life-saving technologies of today aren’t all being grown in test tubes or Petri dishes. Some of them are being 3-D printed.

Since little Garrett Peterson was born, his parents have faced the harrowing ordeal of watching their child just suddenly stop breathing.

Garrett’s mother, Natalie Peterson of Utah says,

“He could go from being totally fine to turning blue sometimes – not even kidding – in 30 seconds. It was so fast. It was really scary.”

Garrett was born with a defective windpipe, a condition also known as tracheomalacia. The condition left the child’s windpipe so weak that even the littlest thing will make it collapse, which cuts off his ability to breathe. Natalie adds,

“When he got upset, or even sometimes just with a diaper change, he would turn completely blue, and that was terrifying.”

After reading Kaiba Gionfriddo’s story they hoped the team of Dr. Glenn Green and Scott Hollister could be able to help their son. So they contacted Dr. Green at the University of Michigan, who specializes in conditions like Garrett’s. Together with his collegue Scott Hollister, who is a biomedical engineer who runs the University of Michigan’s 3-D printing lab, the pair came up with an incredible solution to Garrett’s medical issue – a device that is able to hold open Garrett’s windpipe, at least until it is strong enough to work on it’s own.

3-D printers are an amazing technology. Think of your printer at home. But instead of shooting ink onto a flat page to print a picture or a document, 3-D printers use other materials, sometimes plastic or metal to create three-dimensional objects. 3-D printing has opened a whole new door into manufacturing items, fixing common household problems, and now making leaps and bounds in the medical field. Hollister harnesses the printing technology to create medical devices. The 3D printer that he uses melts particles of plastic and dust with a laser. Already Hollister has built a jawbone for a patient in Italy, as well as helping another baby with a problem similar to Garrett’s. However, Garrett is a lot sicker and his case is a bit more complicated.

At 16 months old, Garrett has not been able to leave the hospital, because each time he would stop breathing, it became a rush to save him. Doctors had gotten to the point that they weren’t sure how much longer they could keep him alive. On January 18th, Garrett was rushed from Salt Lake City to Ann Arbor, Michigan, where doctors Hollister and Green immediately went to work. The first step was to take a CT scan of Garrett’s windpipe so that they could make a 3D replica of it, essentially building a splint for his windpipe. It is a small and white flexible tube that was tailored to fit around Garrett’s windpipe.

Dr. Green says,

“It’s like a protective shell that goes on the outside of the windpipe and it allows the windpipe to be tacked to the inside of that shell to open it up directly.” However, the device is not approved by the Food and Drug administration. It was up to Green and Hollister to try and convince the agency to give them an emergency waiver to try it because they were “running out of time.” Green adds “His condition was critical. It was urgent and things needed to be done quickly. It was highly questionable whether he would survive and how long he would survive.”

Both received the FDA’s approval and Garrett was scheduled to go in for surgery on January 31st.

Dr. Richard Ohye, who had performed the surgery says that when he opened up Garrett’s chest, he and Dr. Green could see that one of Garrett’s lungs was completely white and his windpipe was collapsed. Dr. Green says “The only time I’d seen a white lung was in somebody that had died.” So they quickly set out to work. Both of the splints fit perfectly in Garrett’s windpipe. After more than eight hours in surgery, both of the splints were secure and in place in the little boy’s windpipe. They allowed air to flow through the windpipe and into the boy’s lungs. His white lung turned pink, and his windpipe stayed open.

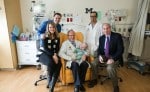

Now 18 months old, Garrett is still in the hospital, but in the weeks since the surgery was performed, the little boy has gotten stronger with each passing day and his parents are thrilled. He has become more interactive, smiles more and plays with his toys more. Garrett’s splint is designed to be able to grow with him as he grows, and will eventually dissolve in his body, as his own windpipe will get strong enough for it to function normally on it’s own.

Dr. Green is hoping to launch a formal study, which would enable him to be able to save the lives of many more children with this amazing technology. He says that this has been one of the most exciting experiences for him since his time at medical school.

Adding,

“We’re talking about taking something like dust and converting it into body parts, and we’re able to do things that were never possible before.”