It is a procedure that may renew hopes for a baby for women with infertility issues. In a first of its kind procedure, a healthy baby boy was born in Japan, after doctors used a new infertility treatment to treat his mom suffering from premature ovarian failure, a condition that affects 1 percent of women in reproductive age.

Primary ovarian insufficiency is a condition that triggers menopausal symptoms, before the age of 40 in women. It also leads to a lack of egg-bearing ovarian follicles. According to the researchers, the 30 year old woman they had selected for their innovative treatment was suffering from the same condition.

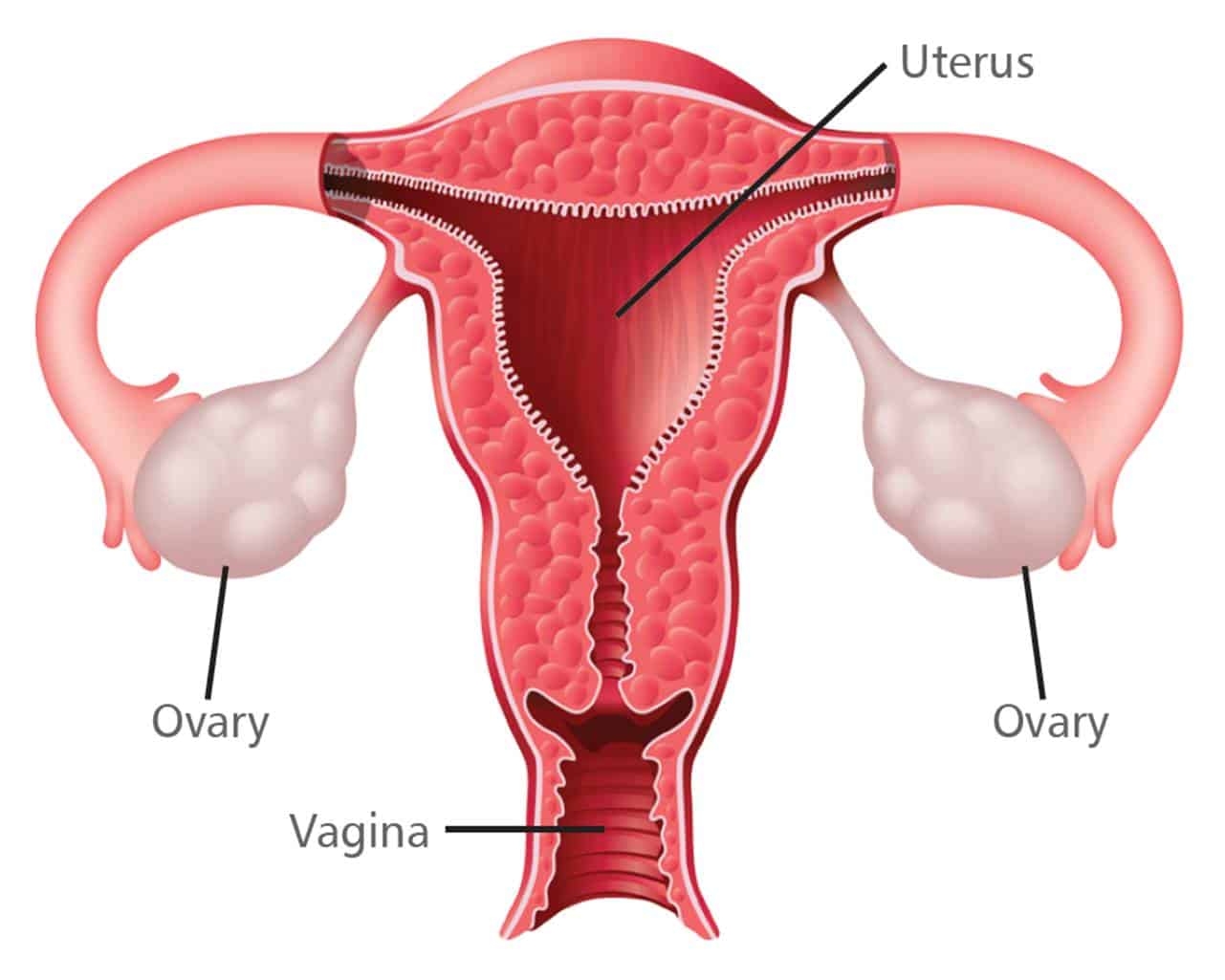

For the procedure, called ovary fragmentation, the mother’s ovaries were removed, cut into small cubes, treated with egg stimulating drugs and then transplanted into the woman’s fallopian tubes. The woman was then given hormones to stimulate egg production.

For the research they selected 27 women suffering from the condition and were able to collect mature eggs from five of them after the procedure. The eggs were artificially inseminated with their husband’s sperm and transferred back into the womb of the women. While one of them has already given birth, another participant is pregnant.

Study author Dr. Kazuhiro Kawamura, director of the Reproduction Center at St. Marianna University School of Medicine in Kanagawa, Japan said,

“I always felt emotional anxiety [about the treatment approach] . . . but when I saw the healthy baby, my anxiety turned to delight. The couple and I hugged each other in tears.”

Kawamura, who collaborated on the research with Stanford University scientists in California added,

“Although we expect our approach to be widely available throughout the world, it is very difficult to repeat it by just following the published paper. We are now thinking of providing a training course for this infertility technique in Japan.”

The researcher said that currently around 1 percent women of reproductive age suffer from this infertility issue and depend on donor eggs to become pregnant. If the procedure could be made widely available it might cost at least $15,000.

“I developed this infertility technique based on my [experience] and knowledge as both a basic scientist and a physician,” said the scientist. “Based on our previous findings, I had confidence that this approach could work clinically.”

The team now wants to see if the same procedure can be used for women with early menopause triggered by cancer chemotherapy or radiation along with other infertile women between the ages of 40 and 45.

Dr. Hailey Hall, an obstetrician-gynecologist at Houston Methodist Hospital in Texas said the procedure was exciting and offered hope to many but the long term affects on mom or baby could only be known later.

Dr. Kawamura however believes that the risk related to the technique is only the common risk associated with laproscopic surgery and it does not affect the egg chromosomes.

It “will be a while before the treatment is commercially available,” Hall said. “It represents hope. The women right now, who are trying to decide if they want to use donor eggs, will have one more thing they can potentially use to have the family they’ve dreamed about.”

It surely is a revolutionary new idea for helping families wishing for a baby.