Each year, more than 300,000 infants die from a congenital anomaly. Many result in conditions like autism, heart defects, Down syndrome, and neural tube defects. Scientists currently do not know what actually causes about half of these defects, and there are many other conditions for which the pathogenic variants are unknown. The Deciphering Developmental Disorders (DDD) study, which was published in the journal Nature, sought to make some headway in these unknown factors and variants.

More than 4,000 Children and Their Families Examined

Conducted by the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute in Cambridge, U.K., the study involved the exome sequencing of more than 4,000 children and their families. At least one member had a severe but undiagnosed developmental disorder. However, the researchers also focused on de novo mutations – mutations that are not present in either parent.

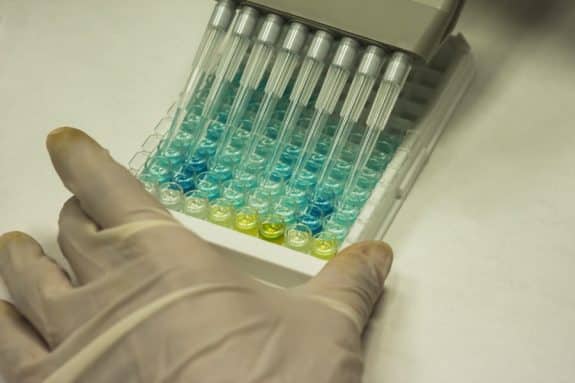

The researchers used exome sequencing because it is one of the most effective ways to selectively sequence protein regions to search for genetic variations in the DNA. Exons also represent about 2.5 percent of the entire human genome, which actually makes examining and sequencing the genome less time-consuming.

Researchers Uncover 14 New Genetic Mutations

Overall, researchers found 94 different genes that were especially likely to have a de novo mutation. Of those, 14 had not been recognized or acknowledged in previous studies as a genetic mutation. Further, the study authors estimated that about 1 in 300 children in the U.K. (about 2,000) are born each year with one of these de novo variations. Worldwide, that estimate was thought to be somewhere around 400,000 affected children each year.

“This study has the largest cohort of such families in the world, and harnesses the power of the NHS, with 200 clinical geneticists and 4,000 patients. The diagnoses we found were only possible because of the great collaborative effort,” said Dr. Matthew Hurles, a co-author in the study. “Finding a diagnosis can be a huge relief for parents and enables them to link up with other families with the same disorder. It lets them access support, plug into social networks and participate in research projects for that specific disorder.”

“Families search for a genetic diagnosis for their children, as this helps them understand the cause of their child’s disorder,” added Professor David FitzPatrick, a supervising author based at the MRC Human Genetics Unit at University of Edinburgh, U.K. “This can help doctors better manage the child’s condition, and gives clues for further research into future therapeutics. In addition to this, a diagnosis can let parents know what the future holds for their child and the risk of any subsequent pregnancies being affected with the same disorder, which can be an enormous help if they want a larger family.”