The British Parliament recently voted to approve a highly controversial fertility procedure that will produce “three-parent babies.” The goal is to hopefully eliminate mitochondrial deficiencies that can severely impact a child’s life, but many fear that this new reproductive technology could be the first step to creating “designer babies.”

Canada is one such country in which that fear is clearly evident.

“There’s no conversation about this. There’s none. We’re talking about a really significant topic, medically. I think, at the very least, we should be having a conversation about it,” Sara Cohen, a Toronto fertility lawyer, told CBC News. “I think part of the problem is that potential punishments [of the procedure] are so severe that it scares people off.”

Mitochondrial disease, which is passed down from the mother, refers to a specific group of disorders that affect the mitochondria—tiny structures found in nearly ever cell of the body. These mitochondria are like powerhouses, converting food and oxygen into energy.

For those with mitochondrial disease—a condition caused by a mutation of the mitochondria—the energy production process is severely disrupted. Once the mitochondria stop providing energy to the cells, the body starts to break down. Cells fail, and then the organs begin to fail. Most children with the disease are unlikely to live past their mid-teens.

“These women have a potentially fatal disease,” Dr. Mark Tarnopolsky, a medical professor at McMaster University in Hamilton, and an expert on the disease, told CBC News. “They essentially have a Sword of Damocies hanging over their head with this disorder, where if they have a fairly high burden of the disorder, they are likely to pass it on to every subsequent offspring.”

There is no cure for mitochondrial disease, but back in 2008, U.K. scientists started researching a procedure that could potentially remove the genetic mutation responsible for mitochondrial disease and keep it from being passed along to a newborn baby. The procedure is now known widely as the “three parent embryo” procedure.

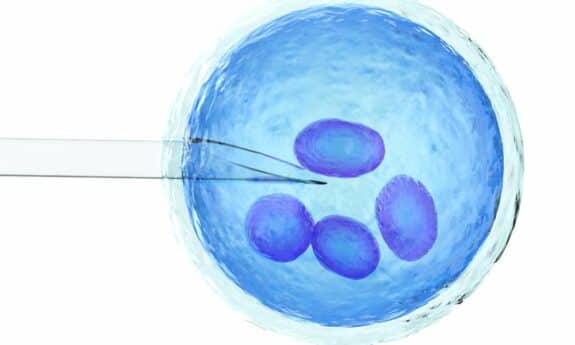

In all actuality, scientists came up with two different procedures that would produce the same results. And both require the use of donor mitochondria from a third party—a female that would give the embryo healthy, functional mitochondria.

In the first procedure, the nucleus of an already fertilized embryo is removed. It then receives a nucleus from the donor, which contains healthy mitochondria. The embryo is then implanted into the mother’s uterus. The second procedure involves removing the nucleus from a mother’s unfertilized egg, implanting the healthy donor nucleus, and then fertilizing the embryo so that it may be implanted.

Either way, the results produce a baby born without mitochondrial disease. And the procedure still ensures that the baby born inherits 99.9 percent of its DNA from its original parents. Only 0.1 percent would come from the donor.

Unfortunately, there are still a number of legal concerns, including the Assisted Human Reproduction Act in Canada which states that no person can knowingly “alter the genome of a cell of a human being or in vitro embryo such that the alteration is capable of being transmitted to the descendents.”

Breaking this law can result in a fine of up to $500,000, a jail sentence of up to 10 years, or both. And because of that, much of Canada’s scientific community would rather wait and see how things go in the U.K. before even discussing the possibility of mitochondrial donation.

“Let’s see what the results show in the next five to ten years,” Dr. Neal Mahutte, president of the Canadian Fertility and Andrology Society, told CBC News. “At some point, people might be confident enough to say ‘Well, maybe we should start doing that in other countries.’”

But all of Mahutte’s concerns are related to Canadian laws. In fact, he places no stock in the idea that MRT would end up leading to “designer babies.”

“I think the reality of what they’re doing in the U.K. is so far removed from that,” he said. “The mitochondrial DNA do not code for any traits at all.”

Which is exactly why Tarnopolsky believes a dialogue will open up so that MRT can, at the very least, be discussed.

“When a sophisticated first-world country like the U.K. deems this appropriate to move forward, I see no reason why that dialogue should not be open, and open soon, in Canada,” he said.

Related Articles: